When we think of an aircraft’s overall shape, we instinctively think of a long fuselage section pointed at both ends, a wide wingspan perpendicular to the fuselage, and a horizontal and vertical stabilizer at the aft section of the aircraft. A shape replicated in anything from a Cessna 172, all the way up to the Airbus A380. Of course, not every aircraft follows this shape. Ultimately, aircraft design shapes are based on many factors, usually related to the aircraft’s size and role.

Fighter jets like the F-16 have a very different shape from that of a Boeing 737, which in turn has a very different shape from an ATR-72. Some shapes are optimized for efficiency, some for stealth, and others for stability or payload capacity. And as materials and technologies evolve, designers sometimes push boundaries into shapes that once seemed unconventional or even impractical. One shape I doubt anyone instantly thinks of when they picture an aircraft is a Dorito. Yet, that is exactly the shape McDonnell Douglas came up with for this aircraft.

Dreaming of a Stealthy Flying Dorito

The ‘Flying Dorito’ (officially the McDonnell Douglas A-12 Avenger II) was an aircraft born out of the US Navy’s desire in the 1980s to leap ahead technologically with a carrier-based stealth strike aircraft. A stealthy aircraft launched from carriers would let the Navy strike high-value inland targets without relying on land bases, penetrate heavily defended areas, and keep aircraft carriers relevant in a future where radar-guided missiles and sensors were rapidly improving.

Its unusual triangular “flying-wing” shape earned it the nickname the Flying Dorito, but the concept was serious: a low-observable bomber that could slip through advanced Soviet air defenses, replacing the aging A-6 Intruder. It promised all-weather precision strike, high survivability, and a modern stealth profile, ambitious features for an aircraft meant to be launched from an aircraft carrier.

Unfortunately, though, this aircraft remained very much on the drawing board. The aircraft never flew; it never even had a completed prototype, only a basic mockup that hinted at what might have been. Years of work produced reams of drawings, wind-tunnel models, and ambitious design studies, but none of it ever translated into a flyable aircraft. As costs mounted and technical challenges piled up, the promise of a revolutionary stealth strike aircraft slowly slipped out of reach. Several reasons led to the quick demise of this futuristic and ambitious design, so what were they?

When Physics Punches Back

Most aircraft’s success is measured by length of service, dispatch reliability rates, passengers carried, and number produced. Probably the most important element of an aircraft’s design, which underpins all these benchmarks and measures, is its physical ability to fly and function as desired. The Avenger II’s biggest enemy actually turned out not to be foreign adversaries but physics and engineering reality.

Trying to make a stealth aircraft rugged enough for catapult launches and hard carrier landings created contradictions: weight soared well beyond limits, composite manufacturing was immature, and radar-absorbing materials struggled in corrosive saltwater environments. Making a flying wing stealthy and carrier-capable was technologically ahead of what the late ’80s and early ’90s industrial base could deliver.

The A‑12 failed physically because its stealth-focused, triangular design conflicted with carrier requirements, making it too heavy and unstable at low speeds. Its composite materials warped in the salty, humid environment, altering aerodynamics and structural stiffness. Combined with underpowered engines, the aircraft couldn’t generate enough lift, thrust, or control for safe takeoff and maneuvering.

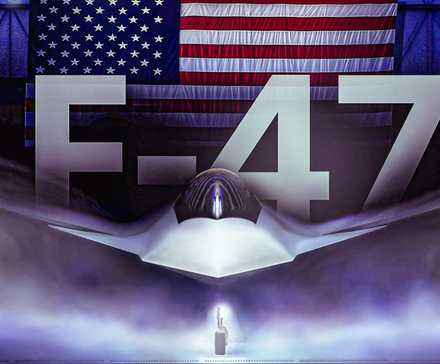

The Real Reason Why Boeing Is Building The F-47 Stealth Fighter And Not Lockheed

Stealth, Speed, and Strategy: Inside the F-47 Revolution.

Money, Mistakes & Mayhem

There’s no doubt that the A-12 was a failure, an extremely expensive one at that. Before it was canceled, the program cost a staggering $5 billion (€3.45 billion), with almost nothing but some drawings and a mockup model of the aircraft. Massive cost overruns contributed to the fact that the original budget estimates were far exceeded due to technical delays and redesigns. Fixed-price contract pitfalls meant contractors faced little flexibility to address unforeseen technical challenges, penalizing them for being honest about problems.

Industrial inexperience likely also played a role; the two main contractors, McDonnell Douglas and General Dynamics, lacked prior experience with stealthy, carrier-capable flying-wing aircraft. That, alongside program mismanagement in the form of weak oversight and poor coordination between the Navy, contractors, and government agencies, exacerbated delays.

This combination likely exacerbated the design and potential manufacturing issues facing McDonnell Douglas and General Dynamics, ultimately leading to the program’s downfall. The enormous expenditures, combined with technical setbacks and management challenges, only added to the mounting pressure on the program and are ultimately the main points judged on reflection today.

Canceled Before It Took Off

In the end, the McDonnell Douglas A-12 Avenger II program only lasted around eight years. The A-12 development effort started when the Advanced Tactical Aircraft (ATA) program began in 1983, with design contracts awarded in 1984. The final ‘main’ contract was awarded on January 13, 1988, to McDonnell Douglas and General Dynamics, but was subsequently canceled on January 5, 1991, by Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney after repeated delays, cost overruns, and missed deadlines.

The Pentagon determined the contractors were in default, citing failure to meet weight, schedule, and performance milestones. By the time of cancellation, no flyable prototype existed, only mockups and incomplete test articles. The program was behind schedule and billions over budget, with no credible recovery plan presented. This was likely a massive contributing factor in the cancellation of the program and a huge pitfall for McDonnell Douglas and General Dynamics cases for keeping the program running.

Cheney refused to authorize further funding because contractors could not demonstrate a realistic path to delivering a functional aircraft. The termination sparked a massive legal battle between the government and contractors over who was at fault, lasting more than two decades. At cancellation, the Navy had already spent roughly $5 billion (€3.45 billion) with nothing operational to show for it. The A-12 remains one of the most financially significant program cancellations in United States defense history.

Top 5 Key Milestones In The Development Of Stealth Technology For Military Planes

There have been major advancements in stealth technology in the last few decades.

The Ghost That Still Haunts the Flight Deck

The A-12 today remains a symbol of overreach. Its principal mission was to replace the Grumman A-6 Intruder, but this never happened. Ultimately, it is a cautionary tale inside naval aviation circles about promising more than technology and industry can deliver. There is still a lingering distrust of risky programs. The program collapse made Navy leadership more cautious about ambitious, unproven designs for carrier aircraft, which carry through even to projects today.

The failure still influences how the Navy structures contracts, manages oversight, and evaluates technological readiness. Many carrier-capable stealth or long-range strike concepts are still measured against the A-12’s high-profile downfall. Ultimately, though, the Navy never actually fully replaced the deep-strike role the A-6/A-12 lineage was meant to fill, leaving a long-term gap in carrier air wing reach.

Billions lost on a program that produced no flyable aircraft remain one of the Navy’s most expensive lessons. The aircraft’s bold concept continues to spark debate over whether a different approach could have yielded a revolutionary platform. Among naval aviators and program managers, the A-12 is still invoked as a warning to be objective whenever weight growth, stealth demands, or schedule slips appear.

What If the Dorito Had Flown?

If the program had been successful and the aircraft had made it through design, testing, and eventually ended up in production, the A-12 would have given the Navy a massive advantage globally, having a true low-observable strike capability, years before aircraft like the F-35C existed. Its long range and internal weapons bays could have revived the A-6 Intruder’s penetrating strike role, reshaping Cold War and post–Cold War naval strategy. This may have led carrier air wings to evolve around a stealth-first philosophy, potentially accelerating unmanned and flying-wing concepts.

Flying the A-12 would have validated high-risk, high-reward development paths, possibly altering how later programs, like the F-35 or Navy UCAVs, were funded and managed. Its ability to strike defended targets from the sea may have altered adversary air-defense development in the ’90s and 2000s. If it had worked, the A-12 might still be flying today in upgraded variants, much like the B-2 or F-117.

Unfortunately, though, none of this ever happened; some may say it was never likely to happen. The legacy today left behind by the McDonnell Douglas A-12 Avenger II is a tarnished reputation in contract management and a single mockup, which is displayed at the Fort Worth Aviation Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. No final aircraft, no production lines, not even a working prototype. The A-12 ended up as more of a ‘Dorito’ than a ‘Flying Dorito’.